The Importance of Segmentation in Understanding Public Opinion to Climate Change and the Low-Carbon Economy

And a critical review of the HSBC Climate Change Index 2007

Peter Winters is President and founder of Haddock Research.

In my last blog, I set myself the challenge of convincing business leaders about the green value of their low-carbon brands. In developing my case, this blog article addresses the critical importance of segmentation – to be able to identify, measure and target those who are concerned about climate change.

IMPORTANCE OF MEASURING PUBLIC OPINION

Public opinion is an important factor in moving the world to a low-carbon economy.

Jared Diamond is probably close to the truth when he writes:

“Businesses have changed when the public came to expect and require different behavior, to reward businesses for behavior that the public wanted, and to make things difficult for businesses practicing behaviors that the public didn’t want. I predict that in the future, just as in the past, changes in public attitudes will be essential for changes in businesses’ environmental practices.” (Collapse, 2005, p.485)

By accurately and insightfully measuring public opinion, market researchers have a vital role in guiding business and government strategy. And yet there is a tremendous amount we do not yet know about how people think, feel and behave towards climate change – and we are in danger of being misled by survey results we do know. To illustrate my argument, I am going to make some critical comments about the information provided by the HSBC Climate Confidence Index 2007.

(These comments are intended to be constructively critical; and we would be delighted to receive constructively critical comments of our work! They should also not imply any criticism of what HSBC is doing with the HSBC Climate Partnership , which looks to be an excellent initiative. Also, whilst it still does not cover segmentation, the analysis in the 2008 report does not have the analytical shortcomings of the 2007 report, which I discuss below. Specifically, the 2008 report does not characterise each country as an average, and it focuses on more robust comparisons between attributes rather than between countries.)

The 2007 UK report summaries the results as follows:

“The HSBC Climate Confidence Index 2007 shows the UK as the least engaged of any of the economies surveyed. People in the UK have the lowest level of concern, the lowest confidence in what is being done today to address the issue, the lowest level of personal commitment, and nearly the lowest optimism about the outcome. A fatalistic view is prevalent, with significant ‘green rejection’, especially in younger age groups.”

But what does this really mean? Are they claiming that all British people are like this? After all, I am British and I don’t recognise myself at all in that description?

Although HSBC has not said it explicitly, their analysis is based on taking the averages of various quantitative measurements. To my mind, there are 4 critical questions one should ask about this kind of survey summary, to do with a) the data distribution around an average, b) the relevance of an average, c) the importance of segmentation and d) reliable measurement of public opinion.

1. THE DATA DISTRIBUTION AROUND AN AVERAGE

First, when given an average, we also need to know what the distribution is around the average. Although we have become very familiar with headlines based on averages such as perhaps “the average age of menopause is 51”, we cannot really make judgements about what it means for an individual without knowing what the distribution is around this average. We need to know what proportion of women reach menopause at the ages of 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 and 55.

As regards the HSBC survey summary mentioned above, we need to know whether all (or almost all) of people in the UK are considered to be fairly unengaged with climate change, or are there some people completely unengaged and others who are pretty committed to tackling this issue?

2. THE RELEVANCE OF AN AVERAGE

Secondly, we should also question whether an average is a reasonable way of describing the data. An average is described as a measure of central tendency (and can be calculated as a mean, median and/or mode), and the normal distribution (also known as the Gaussian distribution, or bell-shaped curve) has long been a core methodological assumption of market research analysis. In my opinion, this is often a grave error!

For example, although true, it is misleading to say that, on average, every person has one testicle and one breast. The obvious first step is to segment people, into men and women, before taking an average! I believe that market researchers commonly make less evident mistakes of this kind. Averages do have an important role in the market researchers’ tool-kit, but they are overused and often misapplied.

As Stephen Jay Gould remarked,

“We still carry the historical baggage of a Platonic heritage that seeks sharp essences and definite boundaries. … In short, we view means and medians as the hard "realities," and the variation that permits their calculation as a set of transient and imperfect measurements of this hidden essence .. But all evolutionary biologists know that variation itself is nature's only irreducible essence. Variation is the hard reality, not a set of imperfect measures for a central tendency. Means and medians are the abstractions.”

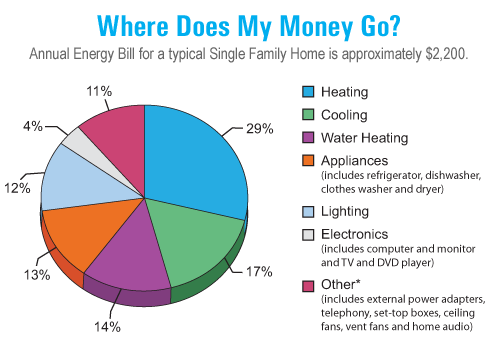

From our Environmental Choices study, we can see that people in Canada, England and the USA are extremely divided in how they think about climate change.

Many people are very engaged with climate change – a group we have termed Climate Citizens. They represent 41% of Canadians, 31% of English people and 28% of Americans. This group is fairly consistent internationally, and have very little in common with the views of the group we have called Sceptics & Uninvolved. 24% of Canadians, 26% of English people and 31% of Americans can be classified as being Sceptics & Uninvolved.

If we look at a whole range of independent attitudes, emotions and behaviours regarding the environment and appeal of low-carbon brands and policies, we can see clear differences between Climate Citizens and Sceptics & Uninvolved. To give just a couple of specific examples, we can see that Climate Citizens are more likely to support restricting airport expansion (see our Government Mandate report) and more likely to be interested in installing a new hydrogen fuel-cell home boiler (see our Fuel Cells report) than people who are either Mild Greens or Sceptics & Uninvolved.

This is not to imply that attitudes towards climate change provide the only, or even most important input, towards understanding every aspect of how people are reacting to the low-carbon economy. We need to look at the survey data to understand this. In real-life, events tend to have multiple contributory factors. [Jared Diamond’s five possible contributing factors to understanding a civilization’s collapse are – 1) environmental damage, 2) climate change, 3) hostile neighbors, 4) friendly trading partners and 5) society’s response to its environmental problems.] For example, the Environmental Choices survey data indicates that contributing factors to public opinion against airport expansion include, a) respondent’s attitudes towards climate change, b) whether the respondent is a flyer or not, and c) whether the respondent lives in England (rather than Canada or the USA; where restricting airport expansion is not currently such a political issue).

3. THE IMPORTANCE OF SEGMENTATION

The comments I have made about averages lead to the conclusion that market researchers need to get much better at understanding how to segment people into relevant groups.

As an analogy to thinking about climate change segmentation, let’s consider people’s attitudes towards God. We should expect clusters of associated beliefs which come with being a believer, an agnostic and an atheist. Surveys which wish to understand religious/ethical opinion (such as on abortion) or behavior (such as buying hymn books) would first need to classify people into these segments.

With regard to climate change, the Environmental Choices survey data indicates that the main groups, Climate Citizens, Mild Greens and Sceptics & Uninvolved – have quite different clusters of beliefs to do with climate change, and their receptiveness to the low-carbon environment. These clusters of beliefs are quite substantial, which seems to reflect the importance of climate change in people’s lives.

The tools that market researchers have to classify people can be created before analyzing the data (a priori), or by using the data to create classifications (a posteriori) or a mixture of both. In the analysis we have done for our Environmental Choices survey, we created the main classifications, a posteriori, using a method called cluster analysis across the international sample. This used as input, 5 variables used to understand people’s attitudes towards climate change – and the analysis grouped people into 3 main types.

What can also be useful is, on particular issue, to classify people into groups on an a priori basis – particularly whether people are users, considerers or non-users of a particular product or service.

4. RELIABLE MEASUREMENT OF PUBLIC OPINION

We also need reliable measurements of public opinion! To make valid inferences between different respondents, or groups of respondents, it is important to have confidence that the measure is reliable. This is not a problem for certain things we would want to measure – such as age and gender.

However, a large number of measurements collected in market research are quite subjective. A popular question type is to ask people to rate something using a “1 to 7” or “1 to 10” scale where “1” is “very poor” and “10” is “excellent”. Responses to these types of questions are not consistent between respondents. My score of “8” may be equivalent to your score of “5”, for a particular attribute.

The scores generated from this type of data are really only robust for measuring between similar attributes or similar products on one scoring task. What you can do with this type of question is then consider which issues are more or less important for a particular individual – and then gross the results up to the group as a whole.

It becomes less reliable to compare between respondent groups, although the level of reliability does depend on how the question was asked exactly, the subject matter and whether there are different cultural norms between the groups. On this last point, comparing between countries can cause major reliability problems since, for example Latin cultures tend to respond to these types of question scales much more positively than those from Northern Europe. I have seen this phenomenon in numerous international studies. In one particularly study a few years ago, the comparison between countries was totally discounted since a literal reading that Italian doctors were exceptionally positive about their medical reps, and that the Dutch doctors were exceptionally negative about theirs, was not at all credible.

Consider now the HSBC Climate Confidence Index 2007 which included the question such as “how much do you agree or disagree with the following statement on a scale of 1 to 7 with “1” meaning disagree strongly and “7” meaning agree strongly (or similar) – ‘Climate change and how we respond to it are among the biggest issues I worry about today.’

How should we interpret the reliability of these measures?

There are 4 main dimensions that the survey considers – which they summarize as relating to Concern, Confidence, Commitment and Optimism – and they report on the “top box” proportions (people who score 6 or 7 on a 7-point scale). Following the argument expressed above, prima facie we should be happy to consider the reliability of the relative agreement between these attributes – that people are more concerned about climate change than confident it can be dealt with (and so on).

However, we should question the reliability of comparing between countries with these questions. Using a “1 to 7” rating scale, on almost any issue I would expect a survey of Brazilians to show higher agreement than a survey of Britons – as is the case with this study. Whilst I am not suggesting that we totally discount this comparison, I am saying that we should be very wary of taking these results at face value. It may be that some “cultural adjustment” analysis could be done to make country comparisons more reliable?!

I am not sure we can ever create perfectly reliable attitudinal measures, but we can certainly look at ways to improve reliability. Personally, I am quite persuaded by the work of Gerald Albaum and his advocacy of the two-stage Likert scale . I think we will also see developments of implicit measurements of attitude in the near future, and look forward to testing their reliability.

End comment

Nearly 100 years ago, Bertrand Russell published his book “The Problems of Philosophy”. In the first chapter he addresses the question of “Appearance and Reality” and asks “Is there any knowledge in the world which is so certain that no reasonable man could doubt it”? He then considers the table he is writing on, and suggests that a painter has to unlearn the habit of thinking of things in a common sense way, and to learn the habit of seeing things as they appear.

In much the same way, I believe that market researchers have the tools to try and understand this intangible thing called “public opinion” much better than we do today. We should unlearn the habit of thinking of public opinion in a common sense way, especially the idea of “the average man”, and provide much more insightful analyses to support businesses and policy-makers.